Congress consists of 100 senators (2 from each state) and 435 members of the House of Representatives, a number that was fixed by the Reapportionment Act of 1929. This act recognized that simply adding more seats to the House as the population grew would make it too unwieldy. Today, each congressperson represents approximately 570,000 people.

Congressional districts

Americans are known for their mobility, and over the years states have lost and gained population. After each federal census, which occurs every ten years, adjustments are made in the number of congressional districts. This process is known as reapportionment. In recent years, states in the West and Southwest have increased their representation in the House, while states in the Northeast and Midwest have lost seats. As a result of the 2000 census, for example, Arizona gained two representatives while New York lost two.

Congressional district lines are usually drawn by the state legislatures (although the federal courts sometimes draw districts when the original plans lose a constitutional challenge). The Supreme Court ruled in 1964 that districts must have roughly the same number of people so that one person's vote in an election is worth the same as another's. This is known as the "one person, one vote" principle. Still, the majority party often tries to draw the boundaries to maximize the chances for its candidates to win elections. In 1812, Governor Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts approved a bill creating such an oddly shaped district that his critics called it a "gerrymander" — a political amphibian with a malicious design. Gerrymandering now refers to the creating of any oddly shaped district designed to elect a representative of a particular political party or a particular ethnic group. In Shaw v. Reno (1993), the Court was extremely critical of oddly-shaped districts such as North Carolina's Twelfth Congressional District, and stated that such districts could be challenged if race was the main factor in their creation. A recent decision (2001) upheld the redrawn boundaries of the North Carolina district.

Members of Congress

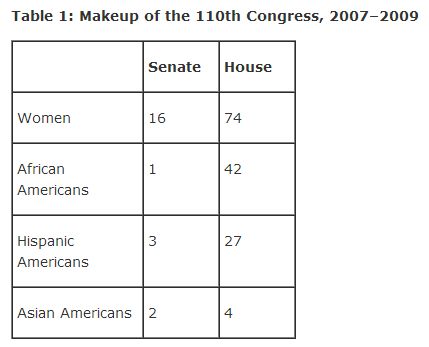

For most of the nation's history, members of Congress have been mainly white males. Beginning with the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the number of ethnic minorities and women in Congress has increased. Elected in 2006, the 110th Congress is the most diverse in American history as shown in Table 1.

Representative Keith Ellison of Minnesota became the first Muslim elected to Congress in 2006 as well.

There has been less change in the occupational backgrounds of the representatives and senators. Many legislators are lawyers or businesspeople, or they have made a career of political life.

Once elected to office, members of Congress represent their constituents in different ways. Some consider themselves delegates, obligated to vote the way the majority of the people in their districts want. A congressperson or senator who takes this position makes every effort to stay in touch with voter public opinion through questionnaires or surveys and frequent trips back home. Others see themselves as trustees who, while taking the views of their constituents into account, use their own best judgment or their conscience to vote. President John Quincy Adams, who served ten terms in the House after he was defeated in the presidential election of 1828, is a classic example of a representative as trustee.

Members of Congress have a clear advantage over challengers who want to unseat them. Current members are incumbents, candidates for reelection who already hold the office. As such, they have name recognition because the people in the district or state know them. They can use the franking privilege, or free use of the mail, to send out newsletters informing their constituents about their views or asking for input. Incumbents traditionally have easier access to campaign funds and volunteers to generate votes. It is not surprising that 90 percent of incumbents are reelected. The situation is not static, however. Legislators run for other offices, and vacancies are created by death, retirement, and resignation. Although term limits, restricting the number of consecutive terms an individual can serve, were rejected by the Supreme Court, the idea continues to enjoy the support of voters who want to see more open contests.

Leadership in the House

The Speaker of the House of Representatives is the only presiding officer and traditionally has been the main spokesperson for the majority party in the House. The position is a very powerful one; the Speaker is third in line in presidential succession (after the president and vice president). The Speaker's real power comes from controlling the selection of committee chairs and committee members and the authority to set the order of business of the House.

The majority floor leader is second only to the Speaker. He or she comes from the political party that controls the House and is elected through a caucus, a meeting of the House party members. The majority leader presents the official position of the party on issues and tries to keep party members loyal to that position, which is not always an easy task. In the event that a minority party wins a majority of the seats in a congressional election, its minority leader usually becomes the majority leader.

The minority party in the House also has a leadership structure, topped by the minority floor leader. Whoever fills this elected position serves as the chief spokesperson and legislative strategist for the party and often works hard to win the support of moderate members of the opposition on particular votes. Although the minority leader has little formal power, it is an important job, especially because whoever holds it conventionally takes over the speakership if control of the House changes hands.

Leadership in the Senate

The Senate has a somewhat different leadership structure. The vice president is officially the presiding officer and is called the president of the Senate. The vice president seldom appears in the Senate chamber in this role unless it appears that a crucial vote may end in a tie. In such instances, the vice president casts the tiebreaking vote.

To deal with day-to-day business, the Senate chooses the president pro tempore. This position is an honorary one and is traditionally given to the senator in the majority party who has the longest continuous service. Because the president pro tempore is a largely ceremonial office, the real work of presiding is done by many senators. As in the House, the Senate has majority and minority leaders. The majority leader exercises considerable political influence. One of the most successful majority leaders was Lyndon Johnson, who led the Senate from 1955 to 1961. His power of persuasion was legendary in getting fellow senators to go along with him on key votes.

In both the Senate and the House, the majority and minority party leadership selects whips, who see to it that party members are present for important votes. They also provide their colleagues with information needed to ensure party loyalty. Because there are so many members of Congress, whips are aided by numerous assistants.

The work of congressional committees

Much of the work of Congress is done in committees, where bills are introduced, hearings are held, and the first votes on proposed laws are taken. The committee structure allows Congress to research an area of public policy, to hear from interested parties, and to develop the expertise of its members. Committee membership reflects the party breakdown; the majority party has a majority of the seats on each committee, including the chair, who is usually chosen by seniority (years of consecutive service on the committee). Membership on a key committee may also be politically advantageous to a senator or representative.

Both houses have four types of committees: standing, select, conference, and joint. Standing committees are permanent committees that determine whether proposed legislation should be presented to the entire House or Senate for consideration. The best-known standing committees are Armed Services, Foreign Relations, and Finance in the Senate and National Security, International Relations, Rules, and Ways and Means in the House. Both chambers have committees on agriculture, appropriations, the judiciary, and veterans' affairs. In 2007, the Senate had 16 standing committees and the House had 20. The House added the Committee on Homeland Security in response to the events of September 11, 2001.

Select committees are also known as special committees. Unlike standing committees, these are temporary and are established to examine specific issues. They must be reestablished with each new Congress. The purpose of select committees is to investigate matters that have attracted widespread attention, such as illegal immigration or drug use. They do not propose legislation but issue a report at the conclusion of their investigation. If a problem becomes an ongoing concern, Congress may decide to change the status of the committee from select to standing.

Conference committees deal with legislation that has been passed by each of both houses of Congress. The two bills may be similar, but they are seldom identical. The function of the conference committee is to iron out the differences. Members of both the House and Senate who have worked on the bill in their respective standing committees serve on the conference committee. It usually takes just a few days for them to come up with the final wording of the legislation. The bill is then reported out of the conference committee and is voted on by both the House and the Senate.

Like the conference committees, joint committees have members from both houses, with the leadership rotating between Senate and House members. They focus on issues of general concern to Congress and investigate problems but do not propose legislation. The Joint Economic Committee, for example, examines the nation's economic policies.

The complexity of lawmaking means that committee work must be divided among subcommittees, smaller groups that focus more closely on the issues and draft the bills. The number of subcommittees grew in the 20th century. In 1995, the House had 84 and the Senate had 69 subcommittees. These numbers actually represent a reduction in subcommittees, following an attempt to reform the legislative process. Although subcommittees allow closer focus on issues, they have contributed to the decentralization and fragmentation of the legislative process.

When a House subcommittee is formed, a chair is selected, whose assignment is based on seniority, and a permanent staff is assembled. Then the subcommittee tends to take on a political life of its own. As a result, there are now many legislators who have political influence, while in the past the House was dominated by just a few powerful committee chairs. The increase in subcommittees has also made it possible for interest groups to deal with fewer legislators in pressing their position. It has become more difficult to pass legislation because the sheer number of subcommittees and committees causes deliberations on bills to be more complicated. Once considered an important reform, Congress's decentralized subcommittees have caused unforeseen problems in advancing legislation.